MUSLIMS IN THE VALLEY – PART 1: THE HAMPSHIRE MOSQUE

http://switchboardmag.com/muslims-one/

By Noor Anwar

March 6, 2013

Bright blue and yellow Nikes, a Peshawri chapal, flip flops, boots of all lengths, even a tiny pair of red, sparkly Wizard of Oz slippers are among the many pairs of shoes lined up outside the entrance to the Hampshire Mosque. The different styles indicate which door to enter from, men on one side, women on the other. Inside, all pray in one room.

The Mosque is situated on one of the outer blocks of Amherst Center. It is surrounded by a variety of shops and restaurants. Its neighbors include a sign-painting shop, a wine and spirits store, and a tattoo parlor. There is only one modest sign outside the entrance that reads “Hampshire Mosque,” with a little crescent moon and star.

Underneath the winding staircase that leads up to the mosque is a tailoring shop owned by a Muslim couple – an American man named Fred who converted to Islam when he married his Turkish wife, Fikriye. They moved from Greenfield to be closer to the mosque. Fred claims that the FBI is staking out the building from the parking lot.

I can faintly hear the voice of the Imam speaking from inside as I take off my shoes outside the ladies’ side door for the jummah (Friday) prayer. I walk inside and am heartily greeted by the other women –Asalam-ul-alaikum – may peace be upon you, they say in unison. I return the greeting, place my backpack next to the others in a corner, and sit down on the oriental carpeted floor beside the women. They all pass me warm smiles, asking if I would like to sit in the front.

“Hello, my name is Semah. Are you new in the area? I have never seen you here at the mosque before.”

Embarrassed, I tell her that I’m a student at the college down the street. I do, however, mention that I visited the mosque during my first semester to celebrate Eid after Ramadan.

“I am from Palestine,” she tells me. “My son just started school at Holyoke Community College. He is liking it very much.”

Semah has a plump, round, cheerful face draped by a baby-blue hijab. She’s wearing matching blue socks. She wants nothing else but to go back to Palestine with her three kids once she has obtained her masters degree in education from UMass. She wants to help improve the education system in her home country.

“I miss it very much.” Her face betrays her thoughts: the pleasure of fond memories and the sadness of not knowing whether she will ever be able to make new ones again. She has not met many Palestinians, but the mosque has filled some of the void she feels.

“We are like a family. They are all my Muslim sisters,” She says, pointing to the other women. “And my brothers,” she points to the men’s side across the yellow room divider. “They have been like father figures for my sons. I very much like how I can bring them here to have good role models in their lives.” Semah resumes listening to the lecture the Arab Imam is presenting on giving to others in the name of Allah.

I spot the owner of the Dorothy slippers. A little six-year-old girl running around her mother and the aunties. She occasionally takes little breaks between her sprinting, pulling down her crop top and standing next to her mother, who performs her prayers – first placing both hands on top of each other across her chest, then bending down halfway, and eventually all the way down with her forehead to the ground. The little girl copies her mother’s every move, occasionally looking up for that she is doing it right. When she thinks that she’s prayed enough, she pulls up her shirt again, rubs her belly and continues twirling around the room.

When the jummah prayer concludes, the aunties go to the kitchenette and fetch large, foil-wrapped trays. They insist I take a paper plate and help myself to the variety of dishes that are spread out on little tables placed next to one another, forming the buffet line. There is every kind of food – pasta, egg fried rice, chicken biryani, boiled eggs with eggplant, meat stew, and barbeque

MUSLIMS IN THE VALLEY – PART 2: THE YOUNG COMMUNITY

“Have you guys had stuff from the halal food cart near the mosque yet?” Ibrahim asks as he adjusts his black and white check-printed Arab fashion scarf. I’m sitting with three other Pakistani boys and an Afghani in the Oak Room, a dining common on the UMass campus with a halal food section.

I have never seen so many brown people in one place since arriving in the valley. “I eat there every day now after maghrib namaz (evening prayer). Those guys are awesome, and they’re doing so well MashAllah. I’ve made them a Facebook page.”

“Dude, I got diarrhea both times,” says Talha, as he takes a big bite of his halal hotdog.

“Dude, you’re from Karachi. Get over it,” quips Ibrahim, scratching his beard.

Ibrahim’s name is on a volunteer list at the mosque for giving lessons to learn the Quran. He is a Hifz-e-Quran, meaning he knows the entire book by heart. He teaches mostly kids who come to the Sunday school he sometimes helps out with; they also learn about things like cleanliness and good etiquette. They take the kids bowling and on little picnics, too. Around fifty kids show up, which can be a little overwhelming in such a small space.

Ibrahim and Saad are both part of the MSA (Muslim Student Association) at UMass Amherst – Saad is also a Hifz-e-Quran. Ibrahim is very involved in the mosque and its activities, and Saad occasionally goes for the jummah prayer. For him, it has more to do with the tradition of actually going with your friends to the mosque on Friday, like back home.

“This guy is always telling me not to go to your Hampshire parties,” laughs Saad, pointing at Ibrahim. “I don’t like discussing religion, it’s become too political.”

“Because as Muslims we don’t want to be tolerated, Saad. We want to be integrated,” Ahmed huffs back.

“But look at what’s happening in our own country, man. If there can be no integration on a national level in an Islamic state like Pakistan, how can we integrate in a place like the freakin’ Pioneer Valley? Religion to me is a really personal thing. I only pray when things are going well and I feel I need to be thankful. Usually people pray only when they need something, like on the night before an exam.” Saad takes a sip of his Vietnamese pho soup.

“I dropped a kayaking course at Hampshire because it was at the same time as jummah” says Talha, running his hand through his Mohawk. He met Ibrahim and Saad at a MSA dinner at the beginning of his first semester, where they told him about the mosque in Amherst. Talha introduced them to Nauman and Arslan, also Hampshire students. He mentions how he eagerly awaits the potluck at the end of jummah at Hampshire Mosque. He likes how the mosque has a real sense of community: there are only sixty people at jummah; back home there were three thousand. To remind him of the azaan(call to prayer), he has downloaded an app on his computer called ‘Guidance’.

Going to the mosque every Friday keeps Talha on track with making sure he is in contact with his faith, in case he hasn’t been praying regularly that week. He appreciates that the khutba (sermon before prayer) is performed in English. Back home he can’t really understand it since it’s in Arabic. He also mentions that there is no fixed Imam (man leading the prayer) at the mosque, and so it gives a chance for different people to lead the jummah.

“Even UMass students! It’s pretty cool. I’ve never seen anything like that back home, where it’s always the same, really old guy. Over here, sometimes the Imam will forget parts when he’s reading the prayer and someone from the back will help him out.”

“They forget it back home sometimes too, ok,” Nauman retorts. Nauman has never gone to the Hampshire Mosque.

“Religion is fairytales taken too literally. If they were told now, an angel would appear holding a divine iPad instead.”

“I’ve never gone to the mosque here, either” says Arslan, the Afghani. “I passed by it during my first year, but it looked kinda sketchy. Honest opinion.” His comment makes me think of the man with the paint-splattered pants I passed as I walked up the stairs to the mosque. He licked his lips and asked me “How ya doin’, baby?”

“If you don’t go to the mosque three times in a row without a valid reason, you’re no longer a Muslim,” Talha says.

“Look, the point is we need play a part at least on our own campuses and try to cater to the college market. Make them see we’re not actually the Taliban. And that Pakistan is not in the Middle East and not all Muslims are Arab! People here are too busy discussing race and gender politics, they don’t want to understand anything else.” Ibrahim talks very fast.

“Just the other day, someone asked me if I spoke Islamic. What does that even mean?” laughs Arslan.

“Well last jummah there was this guy standing outside the mosque so I went outside to talk to him. He asked me if he could come in and pray, and I told him of course! And then I gave him a Quran to take home.”

“Are you sure he wasn’t FBI?” Everyone breaks into laughter.

****

“I’ll be right with you.” Naz, the designated ‘aunty’ of the Hampshire Mosque says to me before going on the side to say her isha (evening prayer). I have come to attend a halaka (discussion on Islam) at the mosque being led by its President of the Board. This week’s topic is an early surah revealed upon the Prophet, telling him of the responsibilities he will be made to face. Naz aunty’s cheerful voice matches the pink, lime green and turquoise embroidered shawl that is draped over her head. She came to the Valley in the late seventies to complete her master’s degree from Mount Holyoke College in developmental psychology, and stayed on to do her doctoral work at UMass. She met her Indian-Muslim husband, who passed away two years ago, in Northampton where he owned an oriental art and textiles gallery.

“I don’t wear a hijab outside the mosque, but that doesn’t mean it’s not the core of my existence” she says, adjusting her red framed glasses. “I don’t feel I need to flaunt my religion; I want everyone to feel comfortable when they talk to me. I see myself, and all of us from the community, as ambassadors of Islam. We need to show that a few misguided people don’t represent all Muslims. All religions have extremist factions and groups.”

Naz became very involved in the mosque after joining the Board a few years ago. Before, she only used to come to pray occasionally. Naz is part of the Interfaith Organization Network, through which she focuses on outreach for the non-Muslim community to dispel misunderstandings and create a sense of community between all the different faiths in the area. Naz always considered herself spiritual, but didn’t regularly practice. She explains how it is all about timing and when you’re seeking for something. If the time is right and you are ripe, you will finally be ready to absorb it.

Naz’s Family

To her disappointment, that time has not yet come for her twenty-three-year-old only son, who has made different choices for his life. She explains that the kind of community her son’s Sunday school mosque had was more rigid and less open to individual identities.

The community never accepted her son and his views, and so it means nothing to him now. He has no affiliation with them or the mosque. She explains how there are different groups now in the area that have built their own communities, because they feel the mosque doesn’t support their views.

“Allah chooses the hearts He opens paths for, and I pray that someday He will open my son’s. So that he will have a good place in the next world.”

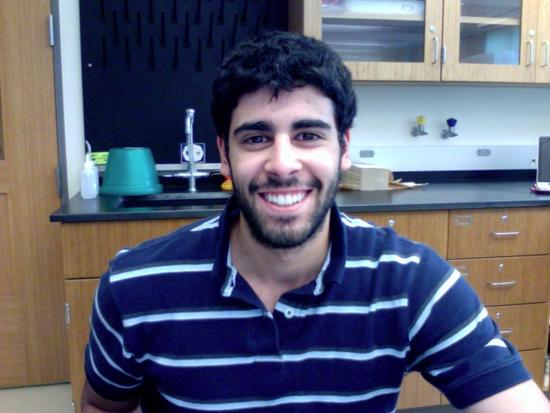

Dr. Ali Hazratji

A suited man with a long, pointy beard wearing a grey blazer, khaki trousers and a white prayer cap walks into the mosque. I recognize him from the poster I saw on the internet, and as the man Ibrahim described as being “really cool.”

“So, I hear that you’re on a wanted list.”

Dr. Ali Hazratjee smiles at me and responds, “Unfortunately, some of us just seem to get more attention.” He laughs. Dr. Ali is the President and one of the earliest members of the Hampshire Mosque when it was created around ten years ago. He is a good-looking man, with high arched eyebrows and a mesmerizing presence. Originally from Gwalior, India, he is now a neurologist in the Springfield area.

“I’m not on any list” he says waving his hand. “Come on, you can’t be on a wanted list and be walking around, now can you?” he asks, sipping his tea. “The truth is always persecuted. It has been since the beginning of time.”

He explains how the drama began two years ago when the mosque put a bid on a piece of property on Harkness Road in Amherst, around the time of the Ground Zero controversy. He says that in the history of Amherst there had never been so many people present at a town meeting as there were on the one regarding the mosque. People even brought attorneys with them. But there were also a lot of people who came to support them, and the Interfaith Organization Network even wrote a letter on behalf of the mosque community.

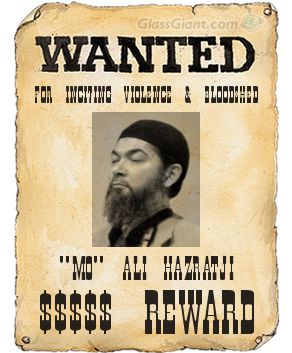

He says there are generalizations made when calling the Valley a ‘liberal’ area, as there are always bigots everywhere, and it’s just that their population here is relatively small. The mosque received hateful and threatening voicemail messages, and people stopped coming to their fundraisers. There is even an anonymous website called the New England Town Crier which targets Islam, the mosque and its employees. They published a poster with Dr. Ali’s face and a “wanted” caption.

“My buddies at the FBI say this website is protected under the right to free speech in the first amendment of the constitution. They are trying to discredit and target us out of ignorance, which is why it is important that we reach out to the community through the discussions we have on Islam.”

“When the lion walks through the forest, the other animals bark. But does the lion stop?” he asks. We have nothing to fear, let the dogs bark. Our history has been through so much worse, this is really nothing in comparison. He smiles and shrugs. He says discrimination has become more localized ever since extreme ‘Islamophobes’ have been elected into the government. “Just yesterday someone put a dead pig inside a mosque in Texas, and I’m sure it wasn’t being gifted as a meal for the Muslims.” He laughs sarcastically.

“If Prophet Muhammad, Jesus or Moses showed up in the US today, they would for sure be put on a terrorist list – with their robes and beards, and because they would speak the same truth. So if I am in fact on some list, then it means I am doing something right.”

This is the second installment of a three part series profiling the Muslim community in the Pioneer Valley. Read the first installment here. Switchboard will publish the final installment of this series on Wednesday, March 27. Noor Anwar is generously contributing selected segments from a larger work on Valley Muslims that she reported last year.

MUSLIMS IN THE VALLEY – PART 3: COMMUNITY IN THE MARGINS

“My partner went to Hampshire, it’s such a cool place!” Ty Power, 42, sips his dark French roast coffee at the Bridge Café at Hampshire College. He has a brown beard, and is wearing a corduroy shirt with a dark, plaid print. He has hearing aids on both his ears, and his right earlobe bears a little silver earring. “I converted to Islam when I was fifteen.”

Ty grew up with a single mother who ran an English language center in Tampa, Florida. His mother’s array of students conditioned Ty to be accepting and open-minded of other cultures and religions. He mentions how it is different for kids these days who are so influenced by and dependent upon a misinformed media as their only source of knowledge about the world. There were a lot of mosques in Tampa. That’s where he first became involved in activism for the Muslim community. Many of its members were being arrested and sent to prison for years by the government, without any reason.

Ty slowly saw his activism turn into a search for truth. He read many religious books, but felt the Quran was the one that spoke to him best as a religious text. He wanted to follow a religion that would take a major form in his life. He says there was no ”dramatic moment as such” in which he converted. He remembers it being a natural progression through which he eventually realized that he had already become a Muslim. Surprisingly, his mother did not accept his religious transformation as he had expected.

“So it made sense for me to move to Morocco. I got married when I was eighteen and moved to Casablanca to live with my husband and his family. I also started wearing a hijab. I had my eldest first son over there. But the marriage didn’t work out. Things had gotten really tense between us and then I had a miscarriage, so I just got up and left.”

“Umm, so how did his family react?” I ask.

“Yeah, it was a little weird for them – me being a foreigner and all.”

“But they, umm, must have been very open-minded. You know, with accepting your identities.” I hesitate.

“Ohhhhh! Did I not mention? I’m transgender.”

Ty got involved in the mosque community again when he came back to Florida. But this time it felt different. When praying he didn’t want to wear gendered clothing and wasn’t comfortable with the segregation between men and women. He saw gay Muslims being hurt and rejected by their families, and being told that God would not hear their prayers. ‘Where do you expect them to seek guidance from then?’ Ty asked himself. He couldn’t remember the Prophet Muhammad ever telling someone not to pray, but he was made to believe that he was going to hell.

“In Morocco, it had been comforting for me to see how gender was so separate and rigidly defined. I got away with a lot by wearing the hijab. In Morocco I had been obsessed with wanting to play the role of the perfect wife and mother. But I realized I couldn’t put my religious beliefs away, or my own identity. I was very conflicted.”

Back at the mosque in Florida, a list-serve for gay Muslims was started by an anonymous college student. The response was incredible, with immediate and unexpectedly high membership. Ty knew there had to be other Muslims who felt the same way he did, but he was still shocked to actually see queer and gay Muslims so strongly coming out and uniting. But Ty remembers it took six months for someone to actually post something on it.

Ty now lives in Northampton, Massachusetts where he is a member of the Pioneer Vally Progressive Muslims group. This self-built community is important to him as he has not always felt fully welcome at the mosques in the Valley. “I mean, I haven’t had any bad experiences, but it’s just that feeling. It could totally also be because I am this white guy who doesn’t at all look Muslim.

“It’s funny how nowadays mosques have to be concerned about surveillance from the police as well as religious fanatics! So I understand why they have to be careful. But I have never tried to be overtly open about my sexuality.”

Ty enjoys going to the mosque for the jummah prayer whenever he can find the time. He mostly goes to the mosque in West Springfield as it is larger, and consequently easier to remain unnoticed. He mentions how at the Hampshire Mosque he particularly likes that they have a meal after jummah, something he has never seen anywhere else before, as it allows for the integration of men and women coming together after prayer. He recently heard that some mosques are opening up prayer line formations that are based on gender, so that those who want to stay neutral don’t have to make a choice. Ty remembers how when the Hampshire Mosque was looking for a larger place to relocate they stated one of their concerns as needing more space to separate men and women during prayer. Ty can’t remember that being the case in any of the Prophet Muhammad’s mosques.

His male partner is Jewish. They both believe that it is more important to have the same intentions rather than the same religion. They both share the same understanding of God, and their relationship to and views on religion.

“There are so many different kinds of Muslims too. I know I could never be with a Muslim who drinks and doesn’t pray.”

In the high holiday season, his partner leads singing and chanting at the synagogue and Ty proudly accompanies him there. He knows it is easier for him to accompany his partner to his services, and that it would be difficult for Ty to take him to the mosque. He says that the mosque people would probably single him out as a non-Muslim and not invite him to join in prayer.

“If I could be more involved with the Hampshire Mosque, I don’t think I would have so much of a problem with being gay as much as with my partner not being accepted. I would never let anything stop me from going to pray at a mosque, but there have been times that I myself have felt that I just could not go.”

Once at a Passover dinner, Ty and his partner were seated on the non-alcohol table with some people from the mosque who had also been invited. During the long dinner, the people from the mosque excused themselves for the isha (evening) prayer.

“That was a real moment of crisis for me. Should I get up too? I mean, they know I’m queer but they don’t know I’m a Muslim. But I had heard the call to prayer and I knew I had to go and pray. So I decided to excuse myself as well and join them.”

His concern is that his two sons don’t share the same relationship with Islam that he does, and he thinks this is due to isolation from the mosques. Similar to his own experience, his children have not felt welcomed or been integrated into the communities.

“It is difficult for me to separate what their individual choices are versus the choices that have been decided for them by not being welcomed into the community. Most kids get dragged by their parents to go to church or the mosque to pray, and I’m sad mine never even got the chance to get traumatized by me like that!” He laughs, contemplatively staring down at his cup of coffee.

Ty’s eldest son was in sixth grade when the 9/11 attacks occurred. He has a “super Arabic name” and he was bullied at school. It was an isolating experience for both Ty and his son. Ty didn’t know any Muslim parents whom he could consult for advice, and his son didn’t know any Muslim kids his age to talk to who were most likely experiencing the same discrimination.

“My eldest son’s father isn’t very helpful in this regard either. I won’t call him a terrorist, but he’s definitely an extremist. He tells my son that everything he is doing is haram (forbidden), giving him a very negative and rigid impression of religion, which is totally different from the one I have raised my boys with. He constantly tells my son how what his mother is doing is wrong and that I am going to hell, and that if he supports me, then so is he! So basically he’s telling him that if he loves his mother, he’s going to hell?”

Ty discusses how there has always been a stigma attached to the gay community, but transgender people are beginning to get more religious support in countries like Egypt and Lebanon, even though it is only in the courts. I ask Ty what his ex-husband’s reaction has been to his transition to identifying as male.

“Oh he ain’t down with that!” He laughs, motioning with his finger. “Because in his mind having been married to me before, now a man, makes him gay! Haram! My being male now is a real threat to him.”

This is the final installment of a three part series profiling the Muslim community in the Pioneer Valley. You can read the first installment here, and the second here. Noor Anwar generously contributed selected segments from a larger work on Valley Muslims that she reported last year.